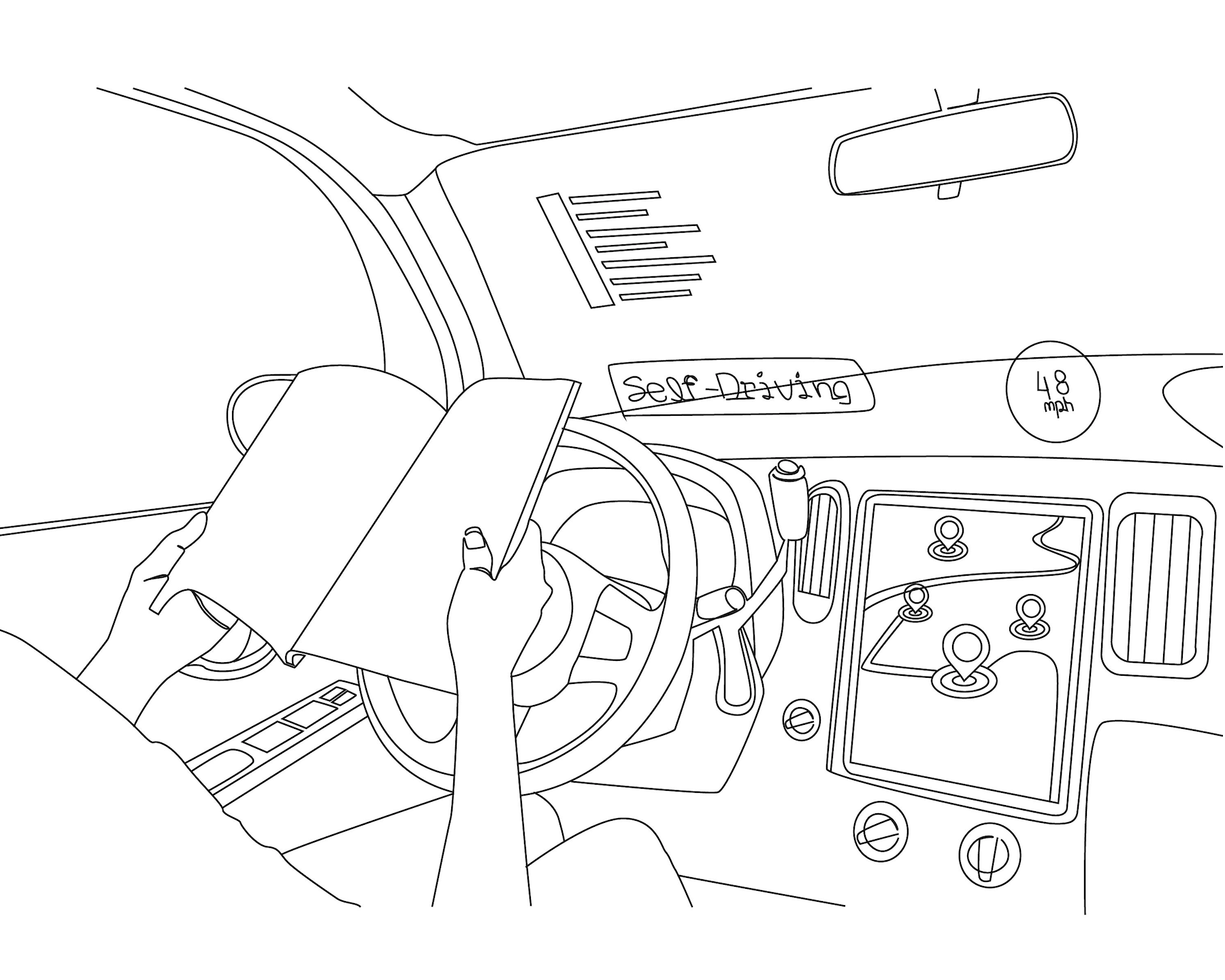

With the new millennium on the horizon, the Disney Channel released two movies with futuristic technology: Zenon: Girl of the 21st Century and Smart House. The former featured self-driving cars, the latter an artificially intelligent house that gains full autonomy, projects herself as a hologram, and manipulates the lives of her inhabitants. Smart House— along with the advent of smart televisions and smart speakers– trained a generation of millennials to be on their best behavior in their homes: something is always listening. Unfortunately, Zenon did not adequately warn us that cars of the 21st century cannot be trusted. Many naively believe their car is merely a tool to transport their person, but modern cars gather significant quantities of data about motorists’ behavior. As cars become more autonomous, the number of sensors and cameras will increase, generating more data points. This data may soon be worth more than the value of the vehicle.[1] It is imperative this industry becomes federally regulated. If we wait until President Clinton takes office, it will be too late.

What Data Do Modern Automobiles Gather?

John Ellis, the former head of technology at Ford, showed CBS News the data streamed in real time from a vehicle to the manufacturer. Ellis said, “with enough data, I can discern patterns that seem to be almost non-existent to the human eye.”[2] New vehicles process up to 25 gigabytes of data every hour and have the power of 20 computers. Most modern cars are also equipped with black boxes that store information about the driver’s speed and brake patterns. This information can be used for insurance purposes, when the vehicle is in an accident, or to inform the driver of necessary vehicle maintenance.

Some drivers correctly assume their car tracks their location, the music they play, and data collected from synchronized smartphones. Motorists may be surprised about the volume of data that is communicated to car manufacturers about how they drive. In some instances, this data is used to improve autonomous driving programs. My car presents a warning if I approach a car too quickly, or if objects are in blind spots when in reverse. The steering wheel vibrates when it assumes I am drifting from my lane. On occasion, I receive a message questioning if I am tired and need to pull over. These features improve safety, but motorist are not always aware of how the sensors work. Cameras, for example, monitor the driver’s eyes to gauge if they are tired based on eyelid movement.[3] Since modern cars are equipped with cameras inside the cabin, motorists must never enter their car in a disheveled state; otherwise, the manufacturer will try to sell a Supercut in the dashboard.

What Are Current Industry Practices?

In 2014, 20 automakers signed a privacy pledge that promised “to provide customers with clear, meaningful information about the types of information collected and how it is used,” and “ways for customers to manage their data.”[4] GM claims data is only shared with consumer consent. Their privacy policy says they may “use anonymized information or share it with third parties for any legitimate business purpose.”[5] GM refuses to identify who the 3rd parties are, and does not define “legitimate business purpose.”

In June 2021, Vice released a report about a company called Otonomo that sells location data of vehicles throughout the world. The company collects 4.3 billion data points per day from over 40 million vehicles. Despite Otonomo’s assurance that the data was anonymized, Vice easily tracked the movement of individual cars and concluded the likely location of the drivers’ homes. Otonomo has an unenforceable provision in its terms of service that prohibits users from identifying individuals from provided data.[6] Unlike cell phone applications, motorists cannot delete location history gathered from their vehicle and often do not know how to disable tracking.[7] Motorists’ data is given to companies like Otonomo from authority derived in self-regulated “privacy pledges,” with vague terms of service, and unrealistic guarantees that data cannot be deanonymized.

Land of the Free, Home of the Data Mined

The United States is light-years behind Europe in data privacy and user protection laws. The U.S. does not have a single, overarching federal law concerning the collection or handling of sensitive data across all industries. There are some regulations for specific businesses, such as laws governing privacy in health care (HIPPA Privacy Rule) and the financial services (The Gramm-Leach-Billey Act).[8] In general, the U.S. allows each state to write its own privacy and data regulations, which is an illogical system for technologies that cross state lines. Privacy rights advocates should challenge federal legislators to adopt several measures found in the European Data Protection Boards Guidelines that were adopted in March 2021. Some provisions the U.S. must incorporate include:

- Language that states, “technologies should be designed to minimize the collection of personal data, provide privacy-protective default settings, and ensure that data subjects are well informed and have the option to easily modify configurations associated with their personal data.”[9]

- Offer privacy by design suggestions such as processing personal data in the vehicle– instead of over cloud services– to allow users to maintain sole control of data.

- Language that explicitly mandates that users provide consent for access to personal data gathered from connected cars. The Guidelines state that nearly all data collected by vehicles will be classified as personal, even when data it is not linked to a specific name but merely describes conditions of the car, such as tire pressure.

- The scope of personal data to be protected to include data: (1) processed inside the vehicle; (2) exchanged between personal devices connected to the car and; (3) collected within the vehicle and sent to outside parties.

- The actors that must receive consent to collect user data including infotainment service providers, telecommunications operators, and driving assistance systems. Legal responsibility differs based on if one is defined as a controller, joint controllers, or processors.[10]

BS Conclusion

In the EU there is “a right to be forgotten,” which is the freedom to have personal information scrubbed from the Internet. In the U.S., we do not even have a right to get out of a Sirius XM contract when you sell your car! I recognize that is not on topic, but I am still recovering from that recent crusade. Anyway, the U.S. lacks a privacy culture that is found in Europe and as a result, federal regulation of connected vehicles is not likely to soon occur. Furthermore, any legislation must overcome dark money, capitalism, and the structure of the U.S. Senate. If you are concerned about your data, I advise you go back to driving your 1992, green, Dodge Shadow. The 90s are back in style so you will be on trend.

![]()

BS

[1] https://www.cbsnews.com/news/carmakers

-are-collecting-your-data-and-selling-it/

[2] Id.

[3] Id.

[4] https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology

/2019/12/17/what-does-your-car-know-about-

you-we-hacked-chevy-find-out/

[5] Id.

[6] https://www.vice.com/en/article/4avagd/

car-location-data-not-anonymous-otonomo

[7] Id.

[8] https://www.iadclaw.org/defense

counseljournal/connected-cars

-and-automated-driving-

privacy-challenges-on-wheels/

[9] https://fpf.org/blog/edpb-draft-guidelines-on-

connected-cars-focus-on-data-protection-by-

design-and-push-for-consent/

[10] https://edpb.europa.eu/system/files/

2021-03/edpb_guidelines_202001_connected_

vehicles_v2.0_adopted_en.pdf