Drones: The Freedom to Never Leave Home and to Always Be Spied On Within It

Have you ever been home and wanted something that weighed less than 5 lbs? Did you want that item in under 30 minutes without dragging yourself to the store– and it is always a drag, isn’t it? What if that same technology could irreparably harm your privacy rights– is that a trade you are willing to make? If you are anything like me, the answer is “YES!”

Many people; however, are not enthused to compromise their privacy for convenience. Privacy rights advocates are concerned about drones because (like all super cool technologies) when in the hands of law enforcement, they can be used for nefarious purposes.

What Are Drones?

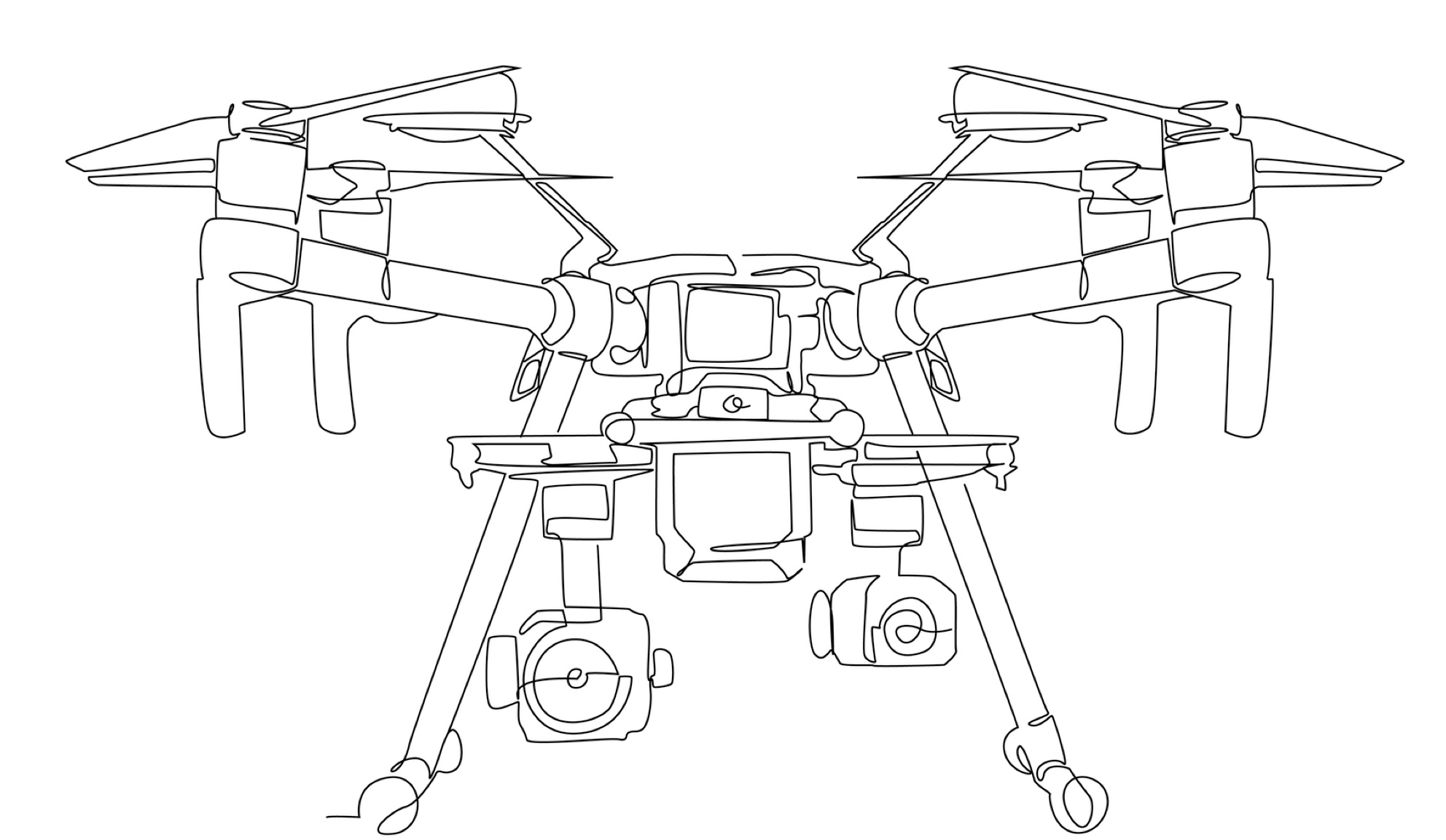

Drones refer to a variety of remotely piloted aircrafts, such as an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), unmanned aerial system (UAS) and small unmanned aerial systems (sUAS). Many drones are equipped with cameras. Although drones have been in the commercial market for only a few years, their popularity has quickly increased.[1] The growing use of drones for commercial and recreational purposes resulted in calls by privacy advocates to regulate their use.

The Fourth Amendment

There is concern that drones will be used by law enforcement to search the private property of citizens without a warrant. The Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution protects “persons, houses, papers and effects” from “unreasonable searches and seizures.” Pursuant to this amendment, law enforcement is generally required to obtain a warrant to conduct a search. There are exceptions to the warrant requirement, such as when a search is conducted incident to arrest.

Fourth Amendment questions arise whenever new technology is used by law enforcement. The Supreme Court addressed whether a search occurred when law enforcement used infrared technology in Kyllo v. United States and tracking devices in United States v. Jones. Although drone technology is relatively new, existing case law is sufficient to address Fourth Amendment concerns. Unfortunately for privacy advocates, it appears drones will be used to legally conduct warrantless searches.

Problems with a Property Rights Approach to Aerial Surveillance

Gregory McNeal of Pepperdine University School of Law offers one recommendation to address fears of warrantless drone searches. He suggests legislators take a property rights approach to aerial surveillance. McNeal argues that under the United States v. Causby, landowners hold some rights to exclude others from airspace directly above their land.[2] He notes that SCOTUS jurisprudence permits warrantless observations if they occur from publically navigable airspace, or from a vantage point accessible by the public. He theorizes that with clearly defined airspace rights, courts can easily resolve claims that drone surveillance violated the Fourth Amendment by asking, “did the police observation take place from a vantage point that violates the landowner’s right to exclude?”[3] If the answer to this question is “no,” would this resolve all Fourth Amendment questions? A property rights approach to warrantless surveillance would do little to prevent law enforcement from flying a drone near the property it wished to observe, either with permission from a neighbor, or on a public road. McNeal’s response is that “local zoning laws could address flights over public land.” It is unclear how local zoning laws would regulate drone use over public land in regards to law enforcement surveillance. With this legislation, courts would still need to seek existing case law to determine if warrantless surveillance by drones violates the Fourth Amendment. Despite the recent development of the technology, there are many cases that address warrantless searches conducted with similar machinery.

Short Review of SCOTUS Precedent

To determine if a constitutionally protected area was searched, the court considers if an individual has exhibited a subjective expectation of privacy and if society is prepared to recognize this expectation as objectively reasonable.[4] Society will recognize one’s subjective expectation of privacy as reasonable against warrantless surveillance if it is conducted with technology not in general use.[5] Millions of drones have been sold to hobbyist and the number grows annually. It is likely the court will find that the drones and affixed cameras are considered general use technologies. Furthermore, SCOTUS held in multiple cases that a warrant is not necessary to observe what is visible to the naked eye.[6] If a drone flies near a property and makes naked-eye observations, the court will likely find the search permissible. In addition to decisions from SCOTUS, two decisions from the 6th Circuit specifically address the use of cameras to conduct warrantless surveillances. In United States v. Houston, the court found that there was no Fourth Amendment violation because the defendant had no reasonable expectation of privacy in footage recorded from a camera that captured views enjoyed by a passersby on public roads.[7] In Anderson-Bagshaw, the court held that use of a common pole camera to conduct surveillance was constitutional because it only captured views easily perceptible from an adjoining lot.[8] These decisions reflect the court’s view that observations made from publicly accessible areas do not require a warrant. Drone surveillance conducted from an adjoining lot or from a publicly accessible location will likely be permitted. Sadly, there is little in the court’s precedent to provide comfort for privacy advocates or future felons.

A BS Suggestion

Before you commit a crime, make sure to close your blinds!

Best Wishes,

![]()

BS

[1]Lucinda Sheen, Drone Sales Have Tripled in the Last Year, Fortune, May 25, 2016 http://fortune.com/2016/05/25/drones-ndp-revenue/

[2]Gregory S. McNeal, Drones and Aerial Surveillance: Considerations for Legislators, Pepp. U. Sch. L., 2014, p. 11.

[3]Id at 13.

[4]Katz v. United States, 389 U.S. 347 (1967).

[5]Kyllo v. United States, 533 U.S. 27 (2001).

[6]California v. Ciraolo, 476 U.S. 207 (1986) and Rileyv. California, 573 U.S. ____ (2014).

[7]United States v. Houston, No. 14-5800 (6thCir. Feb. 8, 2016).

[8]Anderson-Bagshaw, 509 F.App’x 396 (6thCir. 2012).