The subject of this article defies categorization (for this website) and will be tagged as “the law” but the topic is bioethics.

During a bioethics course in law school, we discussed that some deaf couples select for deafness in embryos that are implanted via in vitro fertilization. A room of hearing students could not conceive why anyone would choose “disability.” I am hearing, but I have seen enough episodes of Switched At Birth to know the reaction from my classmates was arrogant and ignorant. One hallmark of privilege is never considering how people have their being outside the status quo. Hearing people do not often contemplate what life is like for the deaf, yet believe their opinions correct when based solely on how they experience the world.

On a break during class, I called my mother and raged. She asked if I said anything during the discussion. “Of course not! I never speak in class.” I just think… and judge. But, I did write this paper. While the subject is not the same as the one raised in class, it does challenge assumptions held by the dominant culture.

Over ninety percent of deaf children are born to hearing parents, and those parents’ understanding of deafness is largely framed by hearing people. I believe that consent to give deaf children cochlear implants is not informed if information about Deaf culture is not presented alongside material about the implants. Some members of the Deaf community say they would never choose to hear and do not label deafness a disability.[1] If parents of deaf children are only presented the perspective of the dominant culture, they may conclude their child must join it to live a fulfilled life.

What Are Cochlear Implants? – A Technical Breakdown

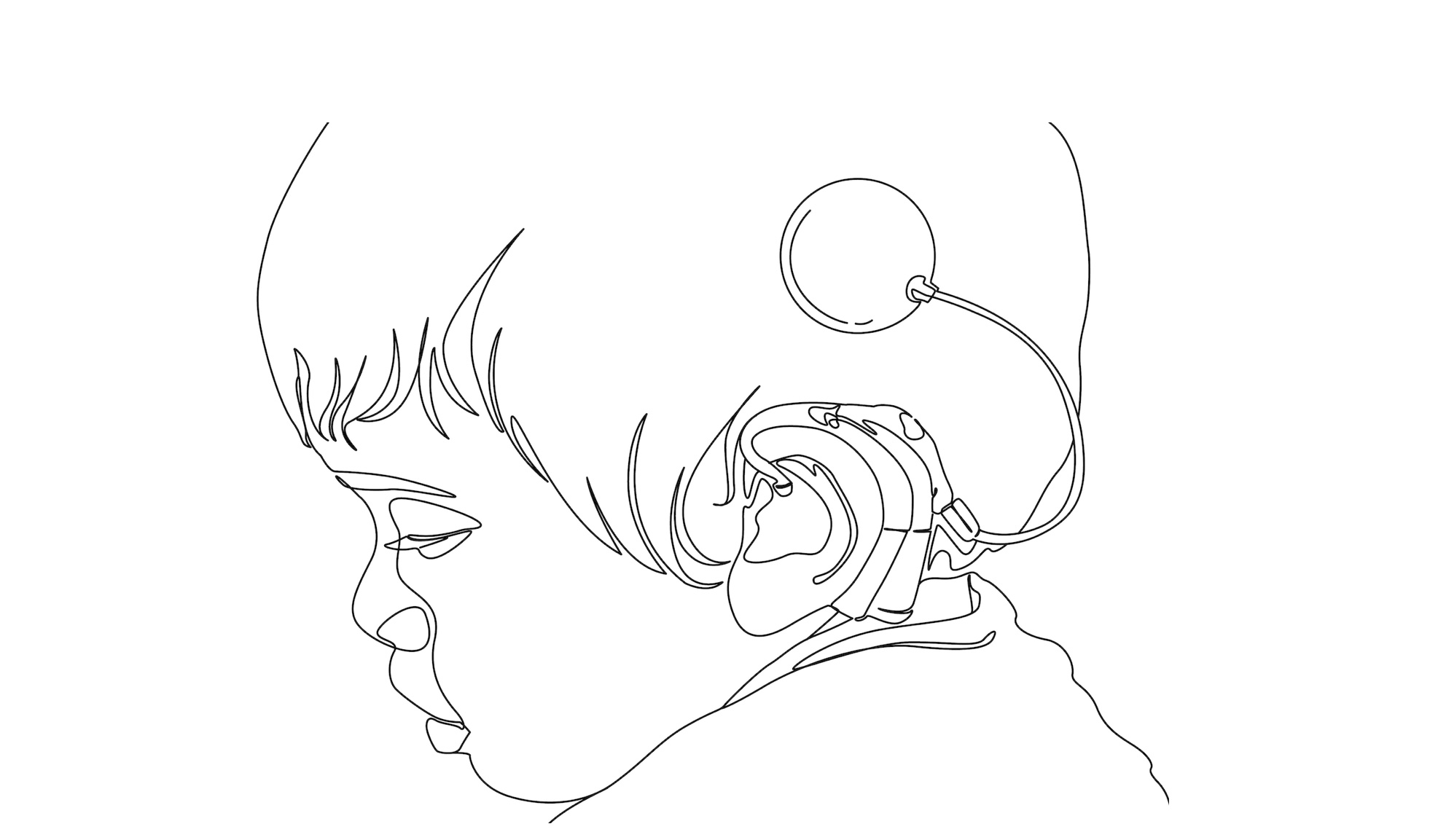

Cochlear implants are electronic devices that are surgically inserted in the inner ear. Whereas hearing aids amplify sound, cochlear implants communicate to the auditory center of the brain to perform the functions of the damaged portions of the ear. Unlike hearing aids, cochlear implants do not depend on the residual hearing of the patients and sound is not amplified. Implanted persons are still deaf and their brains have to learn how to interpret what they hear.[2]

The external part of the ear, the pinna, captures sound that travels through the ear canal and strikes the eardrum, the tympanic membrane (TM). These sound waves cause three bones in the middle of the ear– the ossicles– to vibrate one at a time in a wave. The TM and ossicles compose the middle ear [3]

The cochlea is found beyond this system in the inner ear and is a bony structure that contains the auditory system necessary to hear. The central part of the cochlea has a fluid filled membrane called the cochlear duct, which houses the sensory receptor structures. The vibration from the ossicles creates a wave in the cochlea fluid. As the wave travels, the top and bottom of the cochlear duct moves. Auditory receptor cells are found in the cochlear ducts and contain hair-like structures called cilia, which bend when moved in the fluid and release a neurochemical. The neurochemicals create an impulse similar to a jolt of electricity that travel through the long fibers of the auditory nerve called the 8th cranial nerve. This nerve and the cochlea compose the inner ear.[4] The auditory nerve travels to the brainstem and projects into the auditory centers of the brain.[5]

If hearing loss occurs in the inner ear, it is considered permanent. Often hearing loss in the inner ear happens when the cilia does not bend and fails to release the neurochemical. If the hearing loss is not due to damage to the auditory nerve itself, then a cochlear implant may mitigate hearing loss.[6]

The cochlear implant has two parts: one is surgically implanted and one is placed externally. The internal portion of the implant is composed of a group of wires– the electrodes– that have exposed ends that release electrical discharges. The implant is placed in the lower portion of the cochlea with at least one electrode housed outside of the inner ear in the cavity of the middle ear. A radio wave receiver is also implanted, which directs the electrical energy. Lastly, a magnet is inserted so the external portion of the device can be attached to the user.[7]

The external part of the implant consists of two portions: the first is a microphone and battery source, and the second is a program that facilitates electrode simulation with an external transmitter that directs information to the internal receiver. The external magnet that is used to attach the device is in the external transmitter.[8]

The microphone sends electrical information to a sound analysis center within the internal portion of the implant. This acts as a minicomputer called the speech processor. The sound is then converted to digital form and is manipulated according to strategies that determine electrode stimulation. The process of determining the best electrostimulation approach is a process known as mapping, which occurs approximately one month after implantation. The implant can be remapped if necessary.[9]

What Are Cochlear Implants? Continued (Less Technical)

Improvements in cochlear implant technology occurred rapidly. Children as young as six months old are now implanted. A generation of deaf children have educational and social experiences that are significantly different than their predecessors.[10] There have also been substantial improvements in the equipment implanted in the patient. For example, the inner coil is less rigid than in previous models, which results in less damage when inserted and can preserve residual hearing.[11] Furthermore, implants have begun to be placed bilaterally, which improved the effectiveness of the technology.[12]

Profoundly deaf individuals that are implanted at a young age receive significant benefits over people later implanted. Young recipients have a higher command of spoken language. A study conducted at Indiana University School of Medicine found that patients that received implants at 13 months possessed a similar degrees of vocabulary comprehension as their hearing counterparts. The same study compared 42 unilaterally implanted children with 27 bilaterally implanted children and found that the former were more likely to interact with adults without direct eye contact and to audibly communicate.[13] Outcomes of implants vary widely and between one quarter and one third of implanted children are required to go to a signing environment to fully comprehend and contribute to conversations.[14]

Currently, over 95% of newborns in United States are tested for hearing loss. Prior to these screenings, hearing loss was undiagnosed until the child was– on average– three years old.[15] The delay in testing resulted in a significant loss of time when babies develop communication faculties. Presently, if a baby is found to have hearing loss, audiologists immediately refer the child for further testing. Parents are given information about various services, including cochlear implantation.[16] The implants are considered safe, with few serious side effects. Recipients may experience injury to the facial nerve, develop meningitis, cerebrospinal or perilymph fluid leakage, tinnitus, or taste disturbances, among other things.[17]

Cochlear implants are extremely innovative. Since they are designed to perform the function of a sensory organ, they are considered the first example of neural prosthesis.[18] The implants profoundly impact how a recipient perceives and engages with the world, which is why it is important that decisions about implants are made with a range of information. Before a deaf child receives an implant, parents should consider the context within which the technology was invented and publicly framed. They may decide that despite the promise found in the medically revolutionary device, deafness does not need to be “corrected.”

Section 1: Social Construction

Disability is a social construct.

Disability is a label without a set definition. The word is interpreted in numerous ways and one’s life experiences will shape its meaning. Disability has been described as, “a state of decreased functioning associated with disease, disorder, injury, or other health conditions, which in the context of one’s environment is experienced as an impairment, activity limitation, or participation restriction.”[19] Article 1 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities defines it as persons, “including those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments, which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.”[20] In both definitions, disability is determined by how one interacts with one’s environment. A medical deficiency alone does not meet the definition if one fully participates in society. If society accommodated a medical or biological impairment to a degree that affected individuals could completely engage in society, would those individuals still be labeled disabled? If a deaf person grew up in a city with a majority deaf population, would this person be considered disabled? How one answers the preceding questions is determined by how one interacts with the dominant culture. Disability is a social construct because its definition is not fixed, but is defined communally. The majority culture influences its meaning.

Labels are communally defined and change.

Perceptions of disability are determined by what is considered normal. Normality is based on the characteristics of the majority where a bell-curve is formed. Any extremities on the curve are considered deviations. When the norm is operative, disabled persons are considered deviants; conversely in a society where “imperfect” bodies are normal, the reverse is true.[21]

Nora Groce, the Director of the Leonard Cheshire Disability and Inclusive Development Centre at University College London, conducted a cross-cultural analysis to prove her theory that perceptions of disability vary based on the cultures where they are found. To conduct this study, disability is a constant and the cultural context is the variable. Societies attach meaning to various types of disabilities. For example, in a society where strength and stamina are valued, a person who has difficulty walking will have a reduced social position, the inverse is true in a society that values intellect.[22]

Cultures do not uniformly conceive disabilities similarly.[23] “There are few ideas about disability that are held to be true at all times and by all people.”[24] In most locations, the majority population is hearing; therefore, hearing culture defines normalcy. Subsequently, deafness is usually considered negative in a hearing construct because it is a deviation found in a minority of the population.

What happens if the majority of the population is deaf? On Martha’s Vineyard, a gene for profound deafness spread among individuals between the mid-seventeenth to late nineteenth centuries. As a result, most hearing people on the island learned sign language and deaf individuals were able to fully participate in society without a language barrier.

The role the individual holds in society may also change with modernization. Wheelchairs increase work possibilities for people that require their use– conversely, computers may perform work that is ordinarily done by people with intellectual impairments.[25] Whether a society decides to incorporate individuals with disabilities and to what extent will determine their role in the community.[26]

Harlan Lane, a Deaf community advocate and recipient of the MacArthur Foundation Genius Award, argues that “disability, like ethnicity, is a social construct, not a fact of life, although one property of such constructs is that they appear misleadingly to be a fact of life.”[27] He rejects the disability label for deafness and cites changes of perceptions pertaining to alcoholism and homosexuality to illustrate that labels and classifications are similar social constructions. Until recently, alcoholism was considered the act of voluntary participation in excessive drinking before society determined that alcoholism is an illness. Homosexuality was previously believed to be a moral flaw, crime, and disability that could be corrected. Few still hold those opinions at present. [28]

Labels often change, which means definitions are not objectively true or finite. Deafness does not have to be considered a disability or a hindrance because the predominant hearing culture has given it that label. Many deaf people view deafness as a trait and not a disability. The self-belief that deafness is not a disability should be considered a reason to reject the disability label because, “there is no higher authority on how a group should be regarded than by the members of the group themselves.”[29]

Deaf construction of their identity is in competition with medical professionals who want to promote their own conception of deaf identity.[30]

Medical vs. social model

Disability can be framed in a medical or social model. The medical model conceives of disability in medical terms and the social model considers the individual before addressing the disability.[31] For example, the medical model labels deafness as a biological deficiency that should be medically treated. This model is primarily used in the dominant hearing culture. In a study conducted by Laura Mauldin, participants found that they were socialized to believe the medical interpretation of deafness.[32] When parents receive information about cochlear implants, deafness is framed in medical and neurological terms. The brain is described similarly to a computer where the implant will correct the misfiring frequencies. Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR) screenings that are conducted after failed hearing tests describe a missing signal, and the cochlear implant is the equipment necessary to patch the program. “What accompanies this understanding of deafness is the idea that the brain must be molded in an explicitly nonvisual way.”[33]

One problem with the medical model is that it limits its conception of deafness to a biological aberration without considering the possible value in retaining a biological deviation. “Science refuses to admit the reality of anything that it cannot measure.”[34] The social model, conversely, would label deafness a trait associated with a linguistic minority. Whether a disability is framed by a medical or social model can determine how an individual defines it.

Some argue that the two models are not exclusive and that biological and social realities interact to define disability.[35] Susan Wendell suggests that the physical structure and social organizations of societies significantly affect disability. For example, poor architectural decisions can cause difficulties for disabled persons. She argues that city-planning and architecture are designed with a young adult, non-disabled male in mind.[36] “Thus disability is socially constructed through the failure or unwillingness to create ability among people who do not fit the physical and mental profile of ‘paradigm’ citizens.”[37] The nature and severity of the disability is based on social responses to biological differences.[38] This understanding of disability is reinforced by the UN definition of disability found above. Disability; therefore, should not be defined solely by medical conditions, but also by society’s failure to meet the needs of impaired individuals.[39]

Social stigmatization

To many disabled people, disability is constructed by societal stigmatization of their “otherness.” “For the overwhelming majority [of disabled persons] prejudice is a far greater problem than any impairment; discrimination is a bigger obstacle than disability.”[40] Paul Longmore, a disability advocate who lost the use of both of his hands, stated that disabled persons are often told by counselors and educators growing up that if they “overcome” their disability, they can fulfill their dreams. Longmore argues that this is a lie. “The truth is that the major obstacles we must overcome are pervasive social prejudice, systematic segregation, and institutionalized discrimination.”[41] For the disabled minority, disability may be defined as social stigmatization by the majority instead of as a biological hindrance.

There is no one way to label disability and many factors influence how it is perceived. One of the primary ways disability is framed is by media representation. The dominant culture determines how disability is presented, which can entrench negative stereotypes in public consciousness.

The dominant culture influences media representation of disability, which is framed negatively.

The differences between perceptions of deafness by deaf and hearing people are the result of a power imbalance between the dominant hearing and minority deaf cultures. Cochlear implants are often framed as a “miracle cure” and a sign of “progress,” which suggests that deafness makes one deficient and in need of correction. Deaf scholar and activist Dr. Paddy Ladd cited many examples in his work of where the media portrayed deafness as relating to negative biology as opposed to positive biology. [42]

Positive biology acknowledges that deaf people have developed faculties that are underused by hearing people. For example, the deaf have enhanced visual skills and sensitivity to touch. They are also more globally connected than their hearing peers. Ladd argues that a “high degree of globalism” and “syntactic similarities and plasticity of their languages” makes it easier for deaf people to profoundly relate to others abroad. Conversely, negative biology frames deafness as being medically deficient.[43]

The medical model has traditionally dominated media coverage, and still generally does.[44] Dr. Des Power found that articles about deafness in daily papers reinforced the medical model where deafness is to be corrected to “normalize” deaf people.[45] The medical model is often how deafness is perceived by cochlear implant advocates who frame the implant as a cure which, “demeans Deaf people, belittles their culture and language, and makes no acknowledgment for the diversity of lives Deaf people lead, or their many achievements.”[46]

When cochlear implants were first introduced, media coverage reinforced public perception that deafness was a negative biological condition. A study conducted in Australia between 1986-2003 found that the medical disability model was significantly more common than the socio-cultural model relating to cochlear implantation in children.[47] The study found that human interest articles often promised more than the cochlear implant could deliver. “These are doctors who can make the stone deaf hear music and follow conversations word by word… It is a bionic hearing device that has conquered deafness in more than 200 men, women and children worldwide…and may enable doctors to virtually cure deafness in hundreds of cases.”[48] Additionally, language such as “conquered” further conditioned the public to consider deafness an obstacle rather than a trait that may be accepted or welcomed by deaf people. The authors conclude that since the dominant medical model is prevalent through news coverage of cochlear implants in children, hearing parents of deaf children will be influenced to implant their children, though the extent of the influence is unknown.[49]

The Australian study categorized stories about cochlear implants as either anecdotal or scientific. The former were often sensationalized, personal interest stories that failed to address the science behind the technology. The latter usually reported scientific research that was funded by the implant industry.[50] The anecdotal articles often used emotive language to describe sounds perceived to be of the greatest value to hearing people, such as music and laughter.[51] They also used negative language to describe deafness, such as a headline that read, “Experimental implant rescues man from years of deafness,” which suggested the man needed to be saved. [52] The scientific articles used ambiguous and vague language like “can restore sound” or “varying amounts of success” to carefully not overpromise what implants can do, while also failing to directly address their shortcomings.[53]

The study also textually analyzed word selection used by deaf authors as opposed to hearing. Hearing authors described deafness to convey isolation and fear. They often used the word silence (“utterly silent world”), and characterized deafness as relentless, and without remedy. Deaf authors conveyed the normalcy of deafness; it was construed as a “way of life,” and they discussed a “shared world” with “deaf history and values.” The discussion of cochlear implants by deaf and hearing authors was also starkly different. Hearing authors depicted deafness in medical terms as being “without hope,” “condemned,” “lost.” Deaf authors described cochlear implants with negative connotations as unnecessary and threatening.[54]

Deaf and hearing authors also discuss heredity deafness differently. An article written by a hearing journalist at the BBC summarized a study by the American Journal of Human Genetics: “Signing Increases Deafness Rates” but editorialized the findings negatively. The study found that the number of people that are born profoundly deaf has doubled in the last 200 years and the increase is traced to the creation of sign language. The more that deaf people learned to communicate, the more likely they were to marry and have children that inherited deafness.[55] Alexander Graham Bell was one of the first individuals who studied the link between genetics and deafness. “I believe that deaf people were economic drains in their communities and it was society’s responsibility to find ways to reduce the genetic propagation of deafness.” He raised fears of a “deaf variety of the human race,” which is a perception that is reinforced by articles that associate deafness with negative biology. [56]

Where a hearing writer negatively interpreted increased communication among deaf individuals with a rise in the deaf population, a deaf advocate would observe that deaf people were instrumental in maintaining their marriage rights to counter eugenic activities.[57] The ability of deaf people to create a language to communicate, form families, and communities should be celebrated instead of framed as potentially resulting in adverse effect on the human species.[58]

News articles are often criticized by disability advocates because human interest pieces frequently present stories about individuals who perform physical feats to prove they are not “handicapped” but merely “physically challenged.”[59] The framing reinforces the argument that attitudes, rather than actual disability, hinder impaired persons. Furthermore, human interest stories regularly depict disability as something that must be overcome to integrate disabled people into society. The disabled prove their desire for inclusion in the dominant culture by performing a physical feat.[60] Longmore argues that the scholarly task to combat prejudice is to “raise awareness of the unconscious attitudes and values embedded in media images.”[61]

A study conducted by Farnall & Smith determined that television, film, and journalistic depictions of disabled persons directly impacted feelings about that group by the dominant culture.[62] If a story was framed negatively, participants’ attitudes were adversely impacted. Additionally, contextual information affects individuals’ perceptions of people. For example, an African American standing in a church had a significantly higher positive association than an African American standing in front of a wall with graffiti. If journalists contextually framed disability positively, it could shift perception of the disabled as being an “out group” and can increase social inclusion.[63]

In a study conducted in 2013, 480 participants watched a short film that positively depicted a paraplegic police officer and were asked three questions before and after the screening. The study concluded that nondisabled viewers significantly improved their opinion of the eligibility of a paraplegic person to perform the job of a police officer. The film did not greatly influence the opinions of disabled participants.[64] The authors of the study theorized that mass media often negatively portrays disability, and subsequently, the majority of individuals that consume it develop negative connotations about disabled persons. The general public also rarely interacts with disabled people directly, which greatly increases the likelihood that information gleaned from media will strongly influence underlying beliefs about disability.[65]

Counterargument: Disability is not a social construct.

Disability is not a social construct because people with biological deviation objectively face challenges in most communities. Since deaf individuals are a minority population, deafness requires accommodations in public space. Implants will objectively make interactions in public spaces easier; therefore, one is at a natural disadvantage and is disabled. Though the nuisances of how disability is defined may vary between persons and change over time, biological abnormality determines if one is disabled, which is not decided communally but is a medical reality. Media depictions have no influence over whether disability is biologically or socially defined.

Counterargument: No matter the label, disability is a deficiency.

Disability is a biological impairment that affects how one engages with one’s surroundings. If one is deaf, one will need to learn alternate ways to communicate with the majority population, and may face other challenges. Even if some deaf people do not believe they are disabled, they require accommodation to fully participate in societal activities and are; therefore, labeled disabled.

Some argue that if disabled people do not take all possible measures to reduce the impact of their disability, they should not be afforded public accommodation. Deaf people should take all steps to mitigate the effects of hearing loss. If they opt out of the cochlear implant procedure and do not attempt to normalize with speech therapy, then they should not receive societal accommodations. The government should not pay for interpreters or special education when treatment is not sought.[66] Deafness is a medical condition that can be treated and is; therefore, a disability.

Mary Koch who started the children’s rehabilitation program at Johns Hopkins’ Listening Center believes that deafness is “something that needs to be fixed.”[67] A cochlear implant has been called a “remedy for an unpleasant ailment.” Deafness is a “curable disease.”[68] Deafness is framed medically and the cochlear implant is labeled a cure because deafness is a biological condition. When one is biologically impaired, one is disabled. Some aspects of the disabled label may differ in various locations, but a biological malady is a requisite condition.

Cochlear implant advocates believe that children that are not given implants risk a life of solitude where they are disconnected from larger society and potentially their families. Fewer than 5% of deaf children have at least one deaf parent.[69] Furthermore, hearing parents often have difficulty effectively communicating with their deaf children through sign language.[70] Ellen Rhoades, an auditory rehabilitation specialist, associates profound deafness with isolation. Isolation is reduced when children with cochlear implants are mainstreamed and can be connected to a larger community. She notes that the foundation to reading and writing are oral languages and that hearing languages will better facilitate communication and reading skills in deaf children.[71] Adapting to hearing society requires accepting their technologies to better integrate into the dominant culture. The necessity for cultural integration to reduce separateness illustrates that the deaf are otherwise disadvantaged and disabled. Even if disabled persons are hindered more by institutions and culture than by biological differences, acknowledging the social construct does not remove it. It will still be easier for disabled people to mitigate their impairments to more effectively engage in the dominant culture, which means they are disabled.

Counterargument: The media does not frame disability negatively.

The media may influence public perceptions of disability; however, its framing will not change the label used to describe a biological deviation. Furthermore, public depictions of disability in the media have been nuanced, realistic, and provide new insight to the majority population that may have never been exposed to life with a disability.

In the last 30 years, television has begun to depict disability more positively. In the late 80s, the Facts of Life introduced the first character to primetime television with a disability.[72] Since then, acclaimed shows such as Friday Night Lights, Parenthood, the Sopranos, Lost, Breaking Bad, Glee, and Switched at Birth have cast actors to portray disabled characters.[73] On these shows, the character’s disability is just an aspect of who they are and does not define them. Furthermore, actors such as R.J. Mitte, who has cerebral palsy, and Michael J. Fox, who has Parkinson’s disease, are popular despite their disabilities. In 2016, Nyle DiMarco, a deaf actor from the show Switched at Birth, won Dancing with the Stars and America’s Next Top Model. Disabled actors positively represent disability on television.

Disability has also been sensitively and insightfully depicted in films where several actors won Academy Awards for their work. Daniel Day-Lewis won for My Left Foot; Tom Hanks for Forrest Gump; Marlee Maitlin for Children of a Lesser God; and Eddie Redmayne for the Theory of Everything. These films all contributed to a more nuanced depiction of disability.

News coverage of disabled athletes has also been positive, according to a recent study from Australia. This study examined stories about the Special Olympics that were published between March 19, 2010 and May 7, 2010. Three-hundred and seventy-five articles were analyzed. The majority of the stories only raised disability to provide content for the article. They generally took a social model approach where they emphasized the individual first and not the disability. The stories also highlighted the competitiveness of the athletes and used positive language to describe the athletes such as “stars,” “amazing” and “stellar.”[74]

Although disability is determined medically and not socially, the media does not always depict disability negatively. While there have undoubtedly been insensitive portrayals of disabled persons in the media in the past, that has changed recently. Katie Ellis argues that an increase in disability rights advocacy in the 90s trickled down to influence popular culture.[75]

Conclusion to Section 1! You Are About Halfway Through!

The meaning of disability is determined by cultural factors, which is why there is no absolute definition. The majority culture will define disability based on what it considers normal and members of minority subcultures may reject the label. Biological impairment alone is not sufficient to define disability because social structures will frame its conception. Media depictions will also shape public perception of disability. The ability for the term to be defined and influenced in a multitude of ways is proof of its social construction.

Section 2: Deaf Culture

Deaf Culture is a legitimate subculture where Deaf individuals live fulfilling lives.

“Deaf culture” is a phrase that originated in the 1970s in predominately hearing academic circles.[76] Lowercase deaf refers to an audiological condition where individuals have lost some or all of their hearing. Uppercase Deaf denotes a cultural subset that perceive their experience based on deafness as one similar to other minority cultures.[77] Members of the Deaf world believe they can self-construct a culture and use deafness as a culturally defining characteristic, which they do not perceive as a disability. Deaf culture describes deaf people based on a deaf form of commonality and understanding in how they live their lives and relate to one another.[78] There is a collective name, feeling of community, norms for behavior, distinct values, culture-specific knowledge, customs, social structure, language, and arts that express Deaf experiences.[79] Members of Deaf culture argue that identity is a composite of the biological, psychological and social and it changes throughout one’s life. [80] Deaf culture provides a support system for Deaf individuals in hearing society.[81]

Members of Deaf culture value deafness because it offers a unique way to engage the world. Many Deaf people express that they would never choose to hear because they feel advantaged by deafness.[82][83] They do not automatically frame deafness as a loss, but as a difference or a gain. “Deaf Gain” rejects the frame of hearing loss and describes perceived advantages to deafness in a hearing world.[84] Deaf Gain includes “enhanced spatial cognition, facial recognition, peripheral processing, and speed in detecting images.”[85] With the absence of auditory senses to gauge ones surroundings, enhancements in visual periphery occurs.

In 1900, an international deaf community assembled at the Paris World Fair where a French deaf leader stated that “deaf people around the world know no borders.”[87] Some deaf individuals feel kinship with deaf people globally because they share a common way of experiencing the world. This shared experience is called “DEAF-SAME” and is “grounded in experimental ways of being in the world as deaf people with (what are assumed to be) shared sensorial, social and moral experiences.”[88] This rejects the isolationist view often observed in hearing culture. Additionally, since sign language requires focus on the signer, the signer often expands his visual field to ensure that the person he communicates with is not in danger. This results in increased personal engagement not generally found in the hearing world. “Deaf individuals hold each other in a visual embrace of well-being and safety.”[89]

Members of the Deaf world are part of a minority culture similar to an ethnic group because they meet criteria delineated by social scientists.[90] They have a common language, norms and collective sense of community. Some; however, do not believe that deafness can be culturally defined.[91]

Counterargument: Deaf Culture is not a legitimate subculture.

Some cochlear implant advocates argue that Deaf culture was invented to help deaf people feel better about themselves, and it is not a valid subculture. Deafness is not a trait similar to race and to draw an analogy between surgery to help deaf children pass as hearing and a black child pass as white confuses “restoration of function with cosmetic homogeneity.”[92] They argue that Deaf culture should be classified as a special interest group because its primary concern is not what is in the best interest of society as a whole. Larry G. Stewart, a deaf leader and advocate for ASL opined that “Deaf culture was not discovered; it was created for political purposes.” He argues it is nonsensical to apply the term “culture” to a narrow group of incredibly heterogeneous people.[93]

Conclusion to Section 2!

The Deaf culture perspective is valuable because it rejects the disability label and defines deafness juxtaposed to the majority culture. Deafness can best be understood by those who are deaf rather than by the dominant culture that projects its own meaning to the experience. Even if the concept of Deaf culture is rejected by some, many members of the Deaf world are proud to be deaf and happy to be part of the community. Approval from all members of society is not necessary for the Deaf to self-construct a subculture and engage with each other within it.

Section 3: Informed Consent

Challenges to informed consent in light of mainstream perceptions

Cochlear implants are part of a trend to use technology to “alter, adapt and improve” the natural body.[94] Since children’s identities are developing, parents that make decisions for them will contribute to their child’s adult identity. It is gravely important that before parents’ consent to surgery, they fully understand the costs and benefits of the procedure outside of the dominate hearing paradigm.

Informed consent is rooted in the moral theory of respect for the autonomy of the decision-maker. For the process to be informed, a certain degree of comprehension must be obtained regarding presented information. Literature provided to parents about deaf children is usually in the medical model with a discussion about the medical risks and benefits of the procedure.[95] This model fails to present information from the social model, which might not perceive deafness negatively, even though it is a biomedical impairment.

Informed consent requires that decisions are made without undue pressure or influence, with no hindrance to reasoning or decision making.[96] Laura Mauldin conducted interviews with staff that perform hearing tests on newborns and parents whose babies were tested. The clinic technicians admitted that parents are most vulnerable after they receive diagnosis and that immediately following failed hearing tests, the clinic provides information about cochlear implants. [97] “They gave us the number and the address and stuff of the implant surgeon. They really wanted us to see the surgeon.”[98] The parents described a series of steps they were told to follow.[99] If parents are given information about cochlear implants when they are most vulnerable, they may feel pressure to choose the procedure. A medical frame of deafness only provides medical actions, which do not consider the resources and experiences of Deaf people. The way deafness is framed for these parents is greatly controlled.[100]

Mauldin calls pre-existing routines that are triggered during disability testing “anticipatory structures.” These structures are designed to foster cooperation with parents and reduce their resistance to medical intervention. Communication techniques are implemented to encourage submission, which are principled on the clinic’s ability to anticipate parental concerns. The author, for example, witnessed clinic staff describe highly medical and scientific information to parents while also suggesting they were doing “emotional work” to create an emotional connotation to information provided.[101] Families are generally unaware that anticipatory structures frame their perception about their child’s diagnosis.[102]

Many hearing people cannot conceive deafness outside of a disability framework. “This is particularly true and traumatic for hearing parents of newly diagnosed deaf infants who grieve for the hearing infant they expected and are very susceptible to the promises held out by cochlear implant programs that they can normalize their child.”[103]

Hearing parents often do not know much about deafness before their child is diagnosed and risk meeting practitioners who portray deafness as a tragedy that can be remedied with their help. It is important that parents do not automatically view deafness as something to be pitied that will result in social stigma if not mitigated. “The child can come to be defined in the medical view by the condition, by loss or deficiency, thereby ignoring many other aspects of the child’s identity, relationships and daily life.”[104] This may increase anxiety in hearing parents who immediately seek and rely on medical remedies.[105]

A study conducted in 2007 found that fewer than half of the 121 centers that responded to a national survey included information about deaf culture and sign language. “The focus of the information presented by cochlear implant centers in their informed consent documents is primarily a medical, audiological, communication, and educational aspects.”[106] The National Association of the Deaf is concerned that parents do not receive unbiased material about the implant.[107] Some parents stated they received information about the deaf community, but were rarely exposed to deaf people who could provide firsthand feedback. For consent to be informed, parents must make their decision without fear that their deaf child will experience an isolated life if not implanted.

Scientists like Walter Nance emphasize “the role of personal choice and the importance of science in offering individuals knowledge from which they can fashion their own decisions about genetics, disability or deafness.”[108] Although medical professionals will approach consent from the medical model and advise parents of surgical risks of the procedure, it would be ethically sound for them to provide parents with information about Deaf culture. Furthermore, if advice is solely presented in the medical model, it may create a conflict of interest. It behooves cochlear implant clinics to have patients receive the implant. If more families know about Deaf culture, they may opt-out of the surgery. Some disability advocates suggest that an independent advisor who is either a deaf or Deaf person provide information to parents in cochlear implant facilities to mitigate the risk of a conflict of interest.[109]

Hearing parents often decide to implant their children because they prefer their own sensory orientation.[110] The theory of sensory politics acknowledges that those “who favor implantation are making a medical decision that forces their own sensory orientation in the world on the world of their children.”[111] Decisions to implant children should not be made before parents consider the value of living outside of the dominant structure. “Alternative ways of being are, in fact, intrinsically and extrinsically valid.”[113]

Conclusion

Parents should be advised of Deaf culture before they implant their children so they are exposed to a view that is not often presented in the dominant culture. Without this information, parents may mistakenly conclude the implant is necessary for their child to live a fruitful life. Parents may ultimately determine that the cochlear implant is in the best interest of their child, and their consent will be truly informed because they considered an alternate perspective. The majority culture might observe “hearing loss” where the minority subculture sees “deaf gain.”

![]()

BS

[1] Robert Sparrow, Defending Deaf Culture: The Case of Cochlear Implants, 13 J of Pol Phil (2005).

[2] Irene Leigh, Cochlear Implants: Evolving Perspectives 4, (Raylene Paludeneviciene et al. 2011).

[3] John B. Christiansen & Irene W. Leigh, Cochlear Implants in Children 45-46 (2002).

[4] Id at 46.

[5] Id at 47.

[6] Id at 48.

[7] Id at 49-50.

[8] Id at 53.

[9] Id at 54.

[10] Leigh, supra at 2.

[11] J.K. Niparko et al., Spoken language development in children following cochlear implantation, 303(15), JAMA (2010).

[12] Leigh, supra at 4

[13] Id.

[14] Des Power, Models of Deafness: Cochlear Implants in the Australian Daily Press, 10(4) J of Deaf Stud & Deaf Ed., 451 (2005).

[15] Newborn Hearing Screenings, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, https://report.nih.gov/nihfactsheets/ViewFactSheet.aspx?csid=104.

[16] Leigh, supra at 4.

[17] Benefits and Risks of Cochlear Implants, U.S. Food and Drug Administration,http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/

ProductsandMedicalProcedures/ImplantsandProsthetics/

CochlearImplants/ucm062843.htm#d.

[18] Olivier Macherey & Robert P. Carlyson, Cochlear Implants, 24(18) Current Biology, R878 (September 22, 2014).

[19] Matilde Leonard et al, The definition of disability: what is in a name? 368(9543) The Lancet (2006).

[20] UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, http://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/

convention/convoptprot-e.pdf.

[21] Lennard J. Davis, Enforcing Normalcy: Disability, Deafness and the Body 29 (1995).

[22] Nora Groce, The Cultural Context of Disability in Genetics, Disability, and Deafness 24-27 (2004).

[23] John Vickrey Van Cleve, Genetics, Disability, and Deafness 3 (2004).

[24] Groce, supra at 24.

[25] Id at 29-30.

[26] Groce, supra at 28.

[27] Harlan Lane, Ethnicity, Ethics, and the Deaf-World, 10 (3) J of Deaf Stud & Deaf Ed., 295 (2005).

[28] Id.

[29] Id at 297.

[30] Linda Komesaroff, Surgical Consent: Bioethics and Cochlear Implantation 49 (2007).

[31] Ten Minute Briefing – The Social Model of Disability, British Red Cross (2009), www.redcross.org.uk/standard.asp?id=58926.

[32] Laura Mauldin, A Diagnosis of Deafness: How Mothers Experience Newborn Hearing Screening 27 (2016).

[33] Id at 53.

[34] Louis Menand, The Science of Human Nature and the Human Nature of Science in Genetics, Disability and Deafness 9 (2004).

[35] Susan Wendell, The Rejected Body 57 (1996).

[36] Id at 60

[37] Id.

[38] Id at 61.

[39] Jan D. Reinhardt, Andrew Pennycott, and Bernd A. G. Fellinghauer, Impact of a film portrayal of a police officer with spinal cord injury on attitudes towards disability: a media effects experiment, 963(8288) Disability & Rehabilitation, 289 (2013).

[40] Paul Longmore, Why I Burned My Book and Other Essays on Disability 130 (2003).

[41] Id at 232.

[42] Linda Komesaroff, Surgical Consent: Bioethics and Cochlear Implantation 1 (2007).

[43] Id at 2.

[44] Power, supra at 451.

[45] Des Power, Communicating about deafness: Deaf people in the Australian Press, 30(3), Aus. J of Comm., 143-152 (2003).

[46] K Lloyd, Cochlear implants: The AAD view, Vicdeaf News, October, 2001.

[47] Komesaroff, supra at 88.

[48] Id at 90.

[49] Power, supra at 458 (2005).

[50] Komesaroff, supra at 93.

[51] Id.

[52] Id at 94.

[53] Id at 97.

[54] Id at 110-111.

[55] Signing Increases Deafness, BBC NEWS, April 28, 2004, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/3665939.stm.

[56] Brian H. Greenwald, The Real “Toll” of A.G. Bell in Genetics, Disability and Deafness 35.

[57] Joseph J. Murray, True Love and Sympathy: The Deaf-Deaf Marriages Debate in Transatlantic Perspectives in Genetics, Disability and Deafness.

[58] Id.

[59] Paul Longmore &Robert Dawidoff, Screening Stereotypes: Images of Disabled People in Television and Motion Pictures 141 (2009).

[60] Id.

[61] Id at 147.

[62] Olan Farnall & Kim A. Smith, Reactions to people with disabilities: Personal contact versus viewing of specific media portrayals. 76(4) Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 659-672 (1999).

[63] Christian von Sikorski and Thomas Schierl, Attitudes in Context Media Effects of Salient Contextual Information on Recipients’ Attitudes Toward Persons with Disabilities, 26(2), Journal of Media Psychology 70-80 (2014).

[64] Jan D. Reinhardt, Andrew Pennycott, & Bernd A. G. Fellinghauer, Impact of a film portrayal of a police officer with spinal cord injury on attitudes towards disability: a media effects experiment, 0963-8288, Disability and Rehabilitation, 289 (2013).

[65] Id.

[66] Bonnie Poitras Tucker, Deaf Culture, Cochlear Implants and Elective Disability, 28(4) The Hastings Center Report, 6-14 (1998).

[67] The Cochlear Implant Controversy, CBS News, June 2, 1998, http://www.cbsnews.com/news/the-cochlear-implant-controversy/.

[68] Power supra at 451 (2005).

[69] Paludneviciene supra at 142.

[70] Id.

[71] Id.

[72] Longmore, supra at 143.

[73] Katie Ellis, The Cultural Politics of Media and Popular Culture: Disability and Popular Culture: Focusing on Passion, Creating Community and Expressing Defiance, Routledge, 80 (2015).

[74] Stephen Tanner, Kerry Green & Shawn Burns, Media Coverage of Sport for Athlete with Intellectual Disabilities: The 2010 Special Olympics National Games Examined, Media International Australia, 107-116 (2011).

[75] Ellis, supra at 80.

[76] Paddy Ladd, Understanding Deaf Culture: In Search of Deafhood, Multilingual Matters, 234 (2003).

[77] Id at xviii.

[78] Paludneviciene, supra at 96

[79] Komesaroff, supra at 43-45

[80] Paludneviciene supra at 95

[81] Dan Hoffman & Jean F. Andrews, Why Deaf Culture Matters in Deaf Education, J. of Deaf Stud.& Deaf Ed., 426–427 (2016).

[82] Thom Patterson, A Hearing Son in a Deaf Family: “I’d rather be deaf” CNN: November 23, 2015 http://www.cnn.com/2015/11/23/living/deaf-culture-all-american-family-cnn-digital-short/#.

[83] Robert Sparrow, Defending Deaf Culture: The Case of Cochlear Implants, 13(2) The J. of Pol. Phil., 147 (2005).

[84] L. Bauman, H-Dirksen & Joseph J. Murray, Deaf Gain: Raising the Stakes for Human Diversity xv (2014).

[85] Id at xxv.

[86] Id at 206-207

[87] Annelies Kuster & Michele Friedner, It’s A Small World: International Deaf Spaces and Encounters (2015).

[88] Id at x.

[89] Id at xxvi.

[90] Lane, supra at43

[91] L.G. Stewart, Debunking the bilingual/bicultural snow job in the American deaf community, 116, Ann Otolaryngol 148-49 (1995).

[92] Thomas Balkany, Annelle V. Hodges, & Kenneth W. Goodman, Ethics of cochlear implantation in young children, 114(6), Otolaryngol Head and Neck Surgery (1996).

[93] Larry G. Stewart, Debunking the Bilingual/Bicultural Snow Job in the American Deaf Community, A Deaf American Monograph 42 (1992).

[94] P. Alderson, Children’s Consent to Surgery (1993).

[95] Merv Hyde & Des Power, Some Ethical Dimensions of Cochlear Implantation for Deaf Children and Their Families, 11(1), J. of Deaf Stud. & Deaf Ed. 105 (2006).

[96] Merv Hyde & Des Power, Informed Parental Consent for Cochlear Implantation of Young Deaf Children: Social and Other Considerations in the Use of the ‘Bionic Ear’, 35 (2), Australian Journal of 121 (2000).

[97] Mauldin, supra at 49

[98] Id at 48.

[99] Id at 50.

[100] Id at 54.

[101] Mauldin, supra at 28.

[102] Id at 29.

[103] Power, supra at 452 (2005).

[104] Komesaroff, supra at 33.

[105] Id.

[106] A. Berg, A. Herb, & M. Hurst, Cochlear implants in young children: informed consent as a process and current practices, 16 American Journal of Audiology, 13-28 (2007).

[107] Christiansen, supra at 303.

[108] Van Cleve, supra at ix.

[109] Merv Hyde & Des Power, supra at 109 (2006).

[110] Leigh, supra at 367.

[111] Id. at 380.

[112] Id.

[113] Id.